Stresses and surprises by Dr Christopher Hobson

Despite being based in Japan, I tend not to write directly about it as much as I plan to. I keep meaning to address this, but have been distracted with other topics. Given that the country is in the news following the weekend’s election, I thought it might be useful to offer some reflections and context.

Shigeru Ishiba became Japan’s Prime Minister at the start of October, replacing Fumio Kishida, whose unpopularity had become increasingly untenable. Ishiba’s gambit of holding snap elections immediately after taking power has failed, with the LDP-led coalition failing to win a majority in the lower house for the first time since 2009.

Jesper Koll contrasts those outcomes:

The last time the LDP lost the majority of lower house seats in 2009, Japan was cheering. There was a real winner - the opposition leader turned Prime Minister, Hatoyama Yukio, started with the highest initial approval rating ever. This time around, the LDP’s loss delivers no real winner. There is no cheering, no sense of victory. Instead, within the LDP rivalries and infighting will intensify; and amongst the ‘winning’ opposition parties the chances of overcoming divisions and differences remain minuscule. Nobody wins, Japan loses.

In this sense, one can identify Ishiba’s failure as a less spectacular version of the disastrous gamble earlier this year by French President Emmanuel Macron. In both cases, the countries are left with reduced capacity to govern at a time when faced with deepening domestic and international pressures.

The most immediate prompt explaining the outcome was increasing frustrating with the ruling LDP over its failure to properly address a series of scandals. The Mainichi editorial judged:

Voters passed a verdict against the LDP for its failure to take responsibility for the issue of money in politics. … The major factor behind the LDP’s defeat is its failure to fundamentally correct the political distortion and arrogance that had intensified since the late former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe returned to power in 2012.

Yet as Kunihiko Miyake, a former Japanese diplomat, observed: ‘This is not a simple political money scandal… It’s much more structural and longer term.’ In a NYT piece, Miyake is one of the analysts quoted who point to well known deeper issues Japan faces, such as a stalled economy and bad demographics. On that topic, I actually have a somewhat unlikely ‘bull case’ for the country, but I will save outlining that for another note. Here I want to identify some other stresses that have been largely overlooked.

Between the immediate frustration with the LDP, and the deeper structural concerns, there are a series of more proximate issues that are worth highlighting. Quietly, it has been a difficult year for Japan. It started badly, with the Noto Penisula earthquake on 1st January, and a runway collision at Haneda airport the following day. A month ago, the same part of Japan experienced torrential rains and flooding. Still trying to recover from the earthquake, the people of Ishikawa were hit with another disaster.

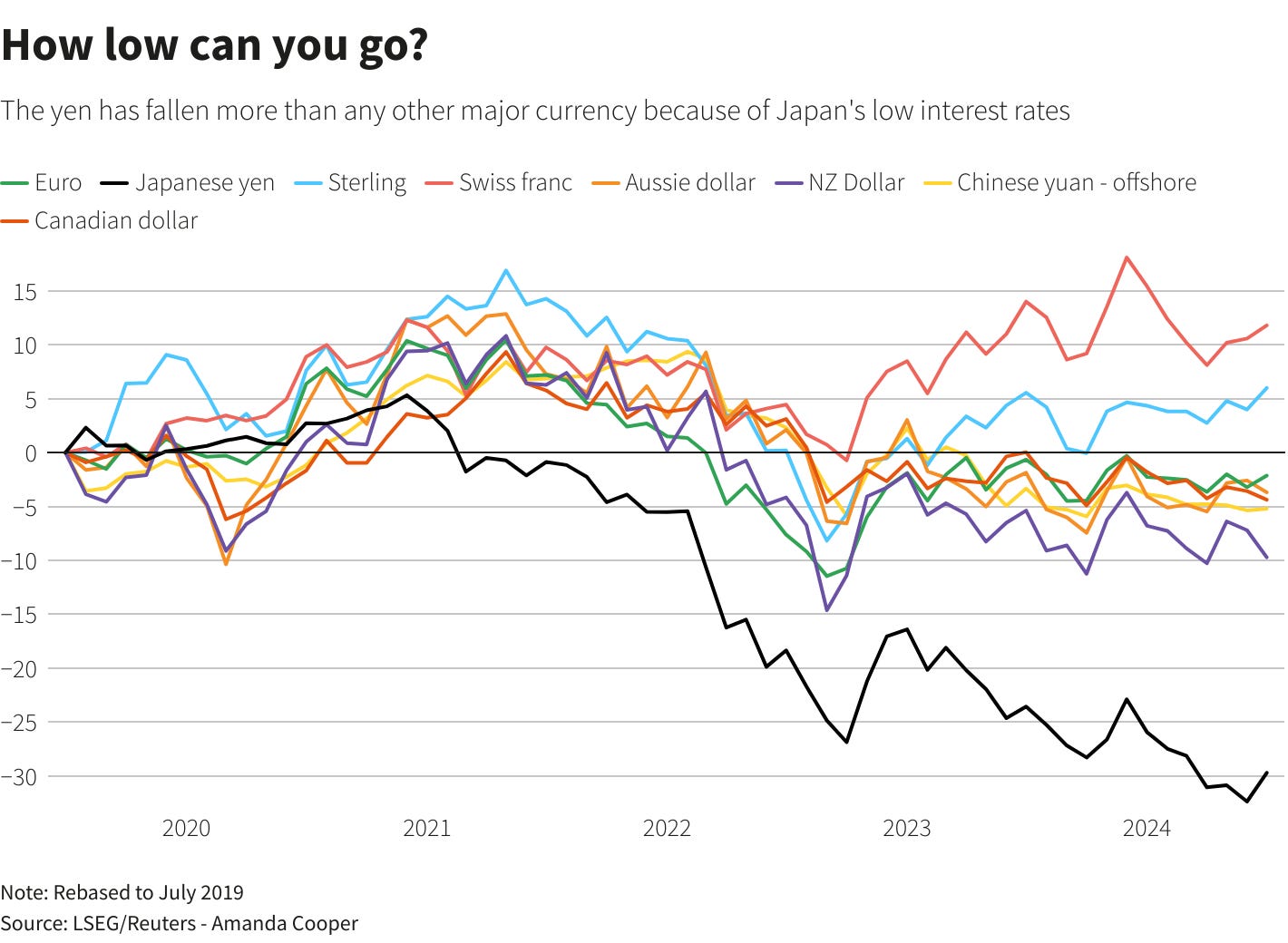

For the first half of the year, one of the most common topics of conversation was about the seemingly never-ending collapse of the Japanese yen. In July, the JPY reached a 38-year low around 161 to the USD. Following some decisive interventions to defend the currency, the result was a remarkable strengthening of the yen. With it, however, came a partial unwinding of the yen carry trade, and Japan’s worst day of trading since Black Monday in 1987. This development certainly made it more difficult to enjoy the yen regaining some value.

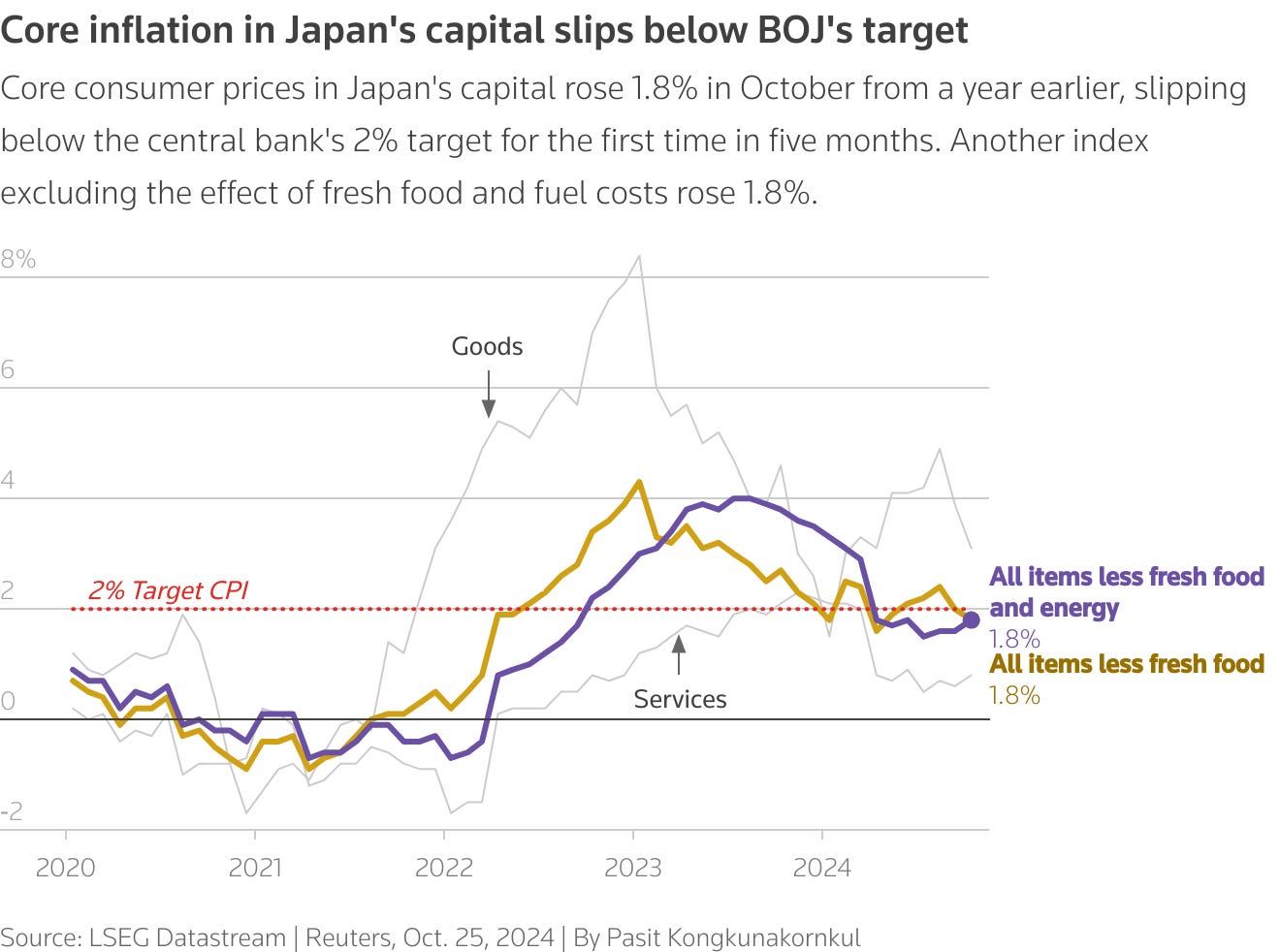

Continuing with the economy, inflation has finally arrived in Japan. Even if it remains low compared to much of the world, it should not be underestimated what a shock to people this has been. After decades of flat prices, the recent uptick is real and noticeable, and is more keenly felt by much of the elderly population.

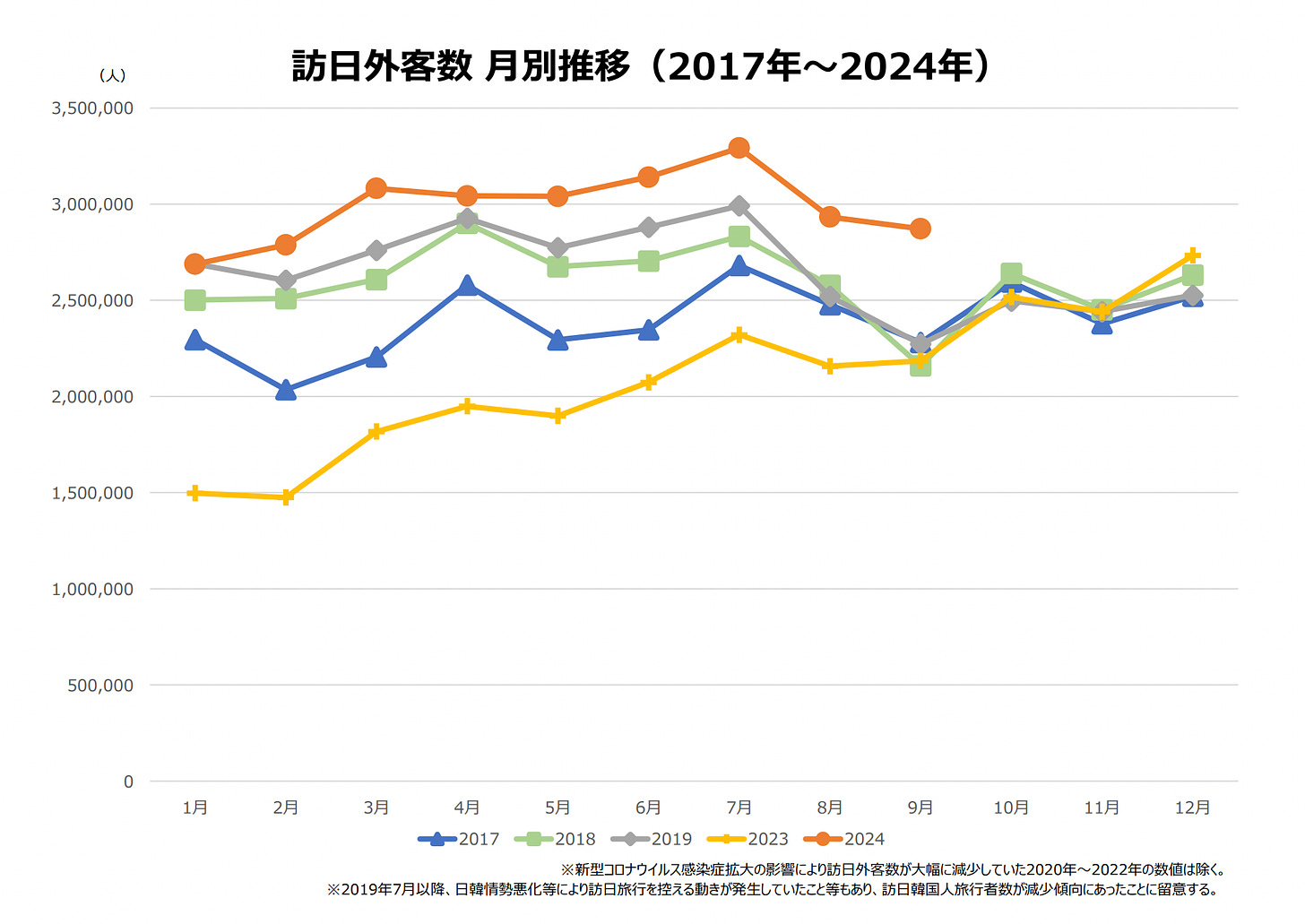

These trends have further crystallised in one of the most noticeable developments of the year, namely, the never-ending surge of tourists. By the end of September, more than 26.88 million foreign visitors had arrived in Japan, exceeding the yearly total for 2023. While it might not be as bad as Greece or Italy, this influx has had a clear impact. It might provide a nice sugar high for the economy, but for the most part, it is not good for the quality of life of people here. While inbound tourists have been gleefully revelling in the weakness of the yen, they have been pricing domestic tourists out of hotels, who have had less capacity for international travel due to that same currency dynamic. The significant increase in monthly visitors for 2024 (see the chart below) suggests that the exchange rate is an important factor contributing to these record numbers.

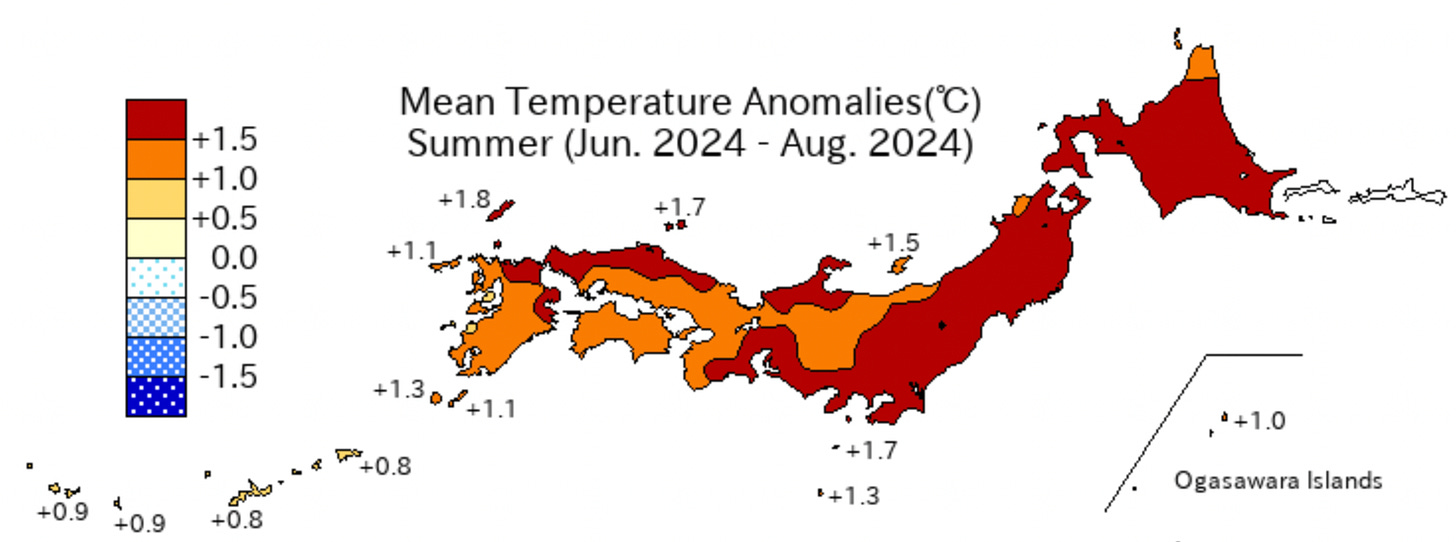

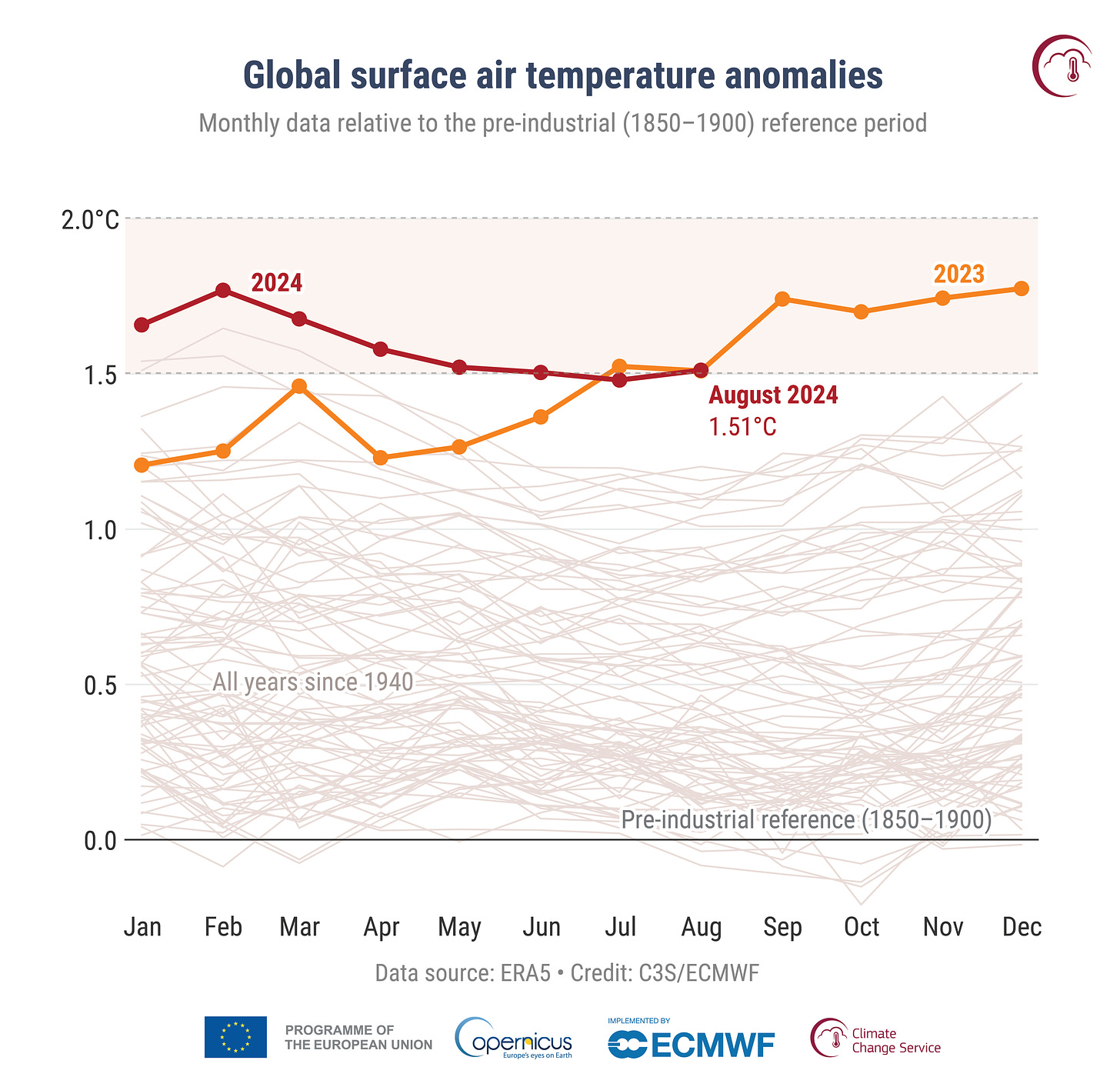

To which can be added one further trend that has been very pronounced this year. It has been hot. Really hot. And really hot a lot of the time. Japan experienced its hottest summer on record, matching the extremes of 2023. When the temperature went above 25 degrees in Tokyo on 24 October, it was the 153rd day of the year that had occurred, the highest on record. This Japan Meteorological Agency map captures the summer:

Many of these trends have powerfully and symbolically come together in the surging price of rice. In the days leading up to the election, it was announced that Tokyo rice prices were up a record 62.3 percent from a year ago. The explanation given is a combination of increased costs related to the yen’s depreciation, being exacerbated by increased demand from tourists and decreased supply because of the excessive heat.

To this list of stresses could be added the concern caused in August by the first-ever alert of a possible Nankai Trough megaquake. While this was lifted a week late, such warnings do not exactly relax people. Neither do incursions by Chinese planes and vessels into Japanese waters and airspace.

I could keep going but the point has been made: it has not been an easy year for Japan. Most of this note I had actually planned in September, as I felt that there was an under-appreciation of these cumulative stresses on the country. Putting them all together, and alongside the manifest shortcomings of the LDP to address the frustrations of the public, the outcome of the election is perhaps not so surprising. One could even suggest that it might have even been over-determined. Given this, Japan remains fortunate that there has not been much uptake in populism and extremism, even if fringe parties did make some gains.

While many of these problems are quite specific to Japan, they are a reflection of dynamics that are posing challenges to governments everywhere. More and more stresses are piling up on systems that have less capacity to respond and reduced freedom to move. Meanwhile, we continue to ignore carbon emission targets and reach new highs in greenhouse gas levels, as the planet cooks.

Returning to the election results, as to where things now stand, this is the initial conclusion offered by one of the closest observers of Japanese politics, Tobias Harris:

Japan is unmistakably in a new era, as politicians and parties and bureaucrats adapt to a system in which power is more diffuse than it has been in years, in which decisions will be harder to reach and harder to implement, and in which abrupt shifts to the distribution of power may be the new normal.

If this proves to be the case, it does not bode well for Japan’s future, given we appear to be entering a pivotal period for politics, economics, technology, and the planet.

This article is originally published on Dr Hobson's blog Imperfect notes on an imperfect world.

Dr Christopher Hobson is a board member of the ANU Japan Institute and Associate Professor at the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific. He is based at the College of Global Liberal Arts, Ritsumeikan University as a Visiting Associate Professor.